How does one create this type of momentum?

Creating momentum and it roles in advancing the motor learning process is also one of the least understood aspects of how to produce increased performance in a short period of time. Rhythm can be used for motor learning within an individual lesson. This rhythm can be sustained from exercise to exercise using progressions within bases of support. The impact is a lesson of motor learning that includes adequate repetitions and multiple learning iterations of “make a mistake, learn the lesson, try it again.”

How can this momentum can sustained during the plan of care cycle over weeks and months, consisting of multiple unique appointments. Individual single session can be linked together to create sustained change over time with a technique borrowed from music composition.

We have already seen in other articles how the use of form assists in structuring of changes efforts over long periods of time. These internal relationships generate momentum. The momentum developed through organizing the internal relationships can be sustained over time by arranging the sub components in relation to the larger goals. This strategic arrangement of goals, sub goals, current reality of those goals and actions create an internal framework of change. Actions taken on behalf of bringing the two data points closer together create the rhythm that established the groove. Rhythm is the result of carrying that form in varying dimensions of time. Each very small dimensions of time is related to another through form, to create components that relate over longer periods of time, resulting in sustainable change efforts.

Arranging time and sound has been the life’s work of Hugo Norden who taught music composition. Again the arts have something to teach us about how to create consistent results. From the book Form: The Silent Language, Norden describes the misconceptions students of music composition must dismiss in order to effectively design music. He describes it as a basic misunderstanding of how the symbols of music and math have undermined the design process. The concept of music produce a misunderstanding of the relationships of notes, and the mechanics of relating and arranging musical notes together into a comprehensive creation that communicates the desired expression.

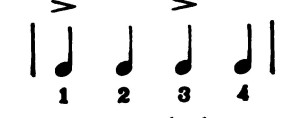

He describes how most children are taught in their music lesson to “count time” from bar line to bar line, thus:

As a result the music composition student, as they are learning to design music naturally follows the same sequencing. In this way, the first note written is followed by the sequence above. In this way it was the preceding note that the following note is based on. However, this burdens the making of the composition as each segment of music becomes isolated and lacks continuity and integrity with the rest of the composition. One stanza is isolated from the overall movement.

Norden further drives the point home as he writes,

“This is a gross misconception which many students never outgrow!” He completes his thoughts by describing the frustration that is common for the musical composer using this approach. Momentum is non existent in the music and the act of creating the music.

We have observed something similar in students of physical therapy, athletic training and in practicing clinicians. In the process of creating results that impact movement, the relationships between components of the plan of care can become categorized. That is they are isolated into silos such that a treatment plan to produce improved sitting to stand function becomes generalized. The internal relationships are lost and as a consequence momentum is undermined. The result is a sense of starting over each time the patient or client arrives for their appointment. The choices made today does not relate to the overall goals of the program.

Progression towards the desired result is lost. Squat pattern training does more than just improve a sit to stand transfer. A squat pattern creates the needed strength to master the increasing complexity of a stride stance balance and wt shifting in asymmetrical stance. And without an adequate foundation in the squat pattern, single limb pattern is very difficult to progress. In this way an opportunity to increase the clients desired involvement in life is missed and the impact of the change effort is temporary as the underlying structure of the approach is to provide only temporary change.

Have a question on this topic, please feel in the box below

[ninja_forms id=6]